Click to subscribe on: Apple / Spotify / Amazon / YouTube / Rumble

Those seeking systemic change often aim to radically overhaul the existing structure and directly challenge the rot they see within. Although history has shown this to be successful at times, it is usually extinguished by the powers that be and perhaps more pragmatic approaches could have brought about the sought change. This is the story told by Dr. Donna J. Nicol, an author and academic, about Dr. Claudia Hampton and her journey to preserve affirmative action. Nicol joins Scheer Intelligence host Robert Scheer to discuss her new book, “Black Woman on Board: Claudia Hampton, the California State University, and the Fight to Save Affirmative Action.”

Nicol sets the scene for her protagonist, introducing the time period in which Black radicalism is at a particular high following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. According to Nicol, Hampton chooses an approach that relies on the tedious path of making inroads with those in power. “[Hampton’s] working in the system not as a Black radical, but as someone who chooses a different way of operating, of a different way of leading, which I refer to in the book as ‘sly civility,’” Nicol tells Scheer.

Self awareness led her down this path, Nicol said. “She understands that her race and her gender are things that can be held against her.”

The radicalism is still relevant, however, and Nicol describes how a person like Hampton is able to render that spirit into meaningful legislation. “We need that agitation on the outside, but we need somebody on the inside to translate this into policy, to translate this into resources for the community,” Nicol said.

Without Hampton, affirmative action wouldn’t have looked the way it ended up. Nicol tells Scheer about Hampton’s time on the California State University board of trustees from 1974 to 1994 and how “during her 20 years on the board, you see the highest increase of students of color, of faculty of color, and those numbers have not been replicated since then.”

Credits

Host:

Producer:

Transcript

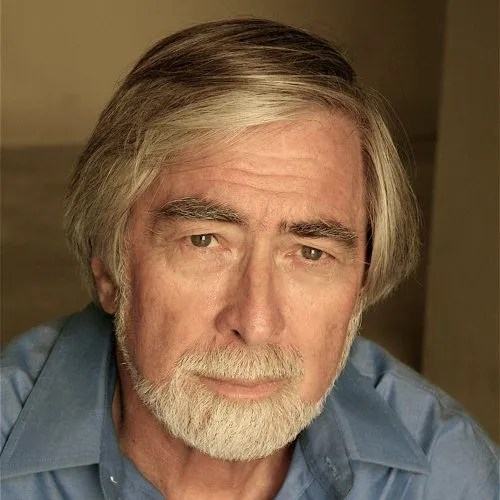

Scheer: Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of Scheer Intelligence, where I hasten to say the intelligence comes from my guest, otherwise I sound like an egomaniac. I didn’t pick the title. I’m really excited to talk to Dr. Donna J Nickel, an expert, got her Doctorate in Education Theories and studying its history, and she’s the Associate Dean of Curriculum and Professor of History at Cal State University Long Beach, which, by the way, has a great journalism school too, and a very good paper. But she did something really interesting. She brought to life a figure who I would not have thought of as a radical Black figure or even a game changer, but a very effective Black woman leader, and her name is Claudia Hampton. I must say, true confession, I teach at USC, so I’m a little bit prejudiced about people connected with it. She got her doctorate at USC, but I actually didn’t know about her until I read your book. My son, Joshua Scheer, who’s also a graduate of USC, who got me interested in this, said, ‘You know, this helps explain Kamala Harris, maybe even Barack Obama.’ And what that idea is, this is not Stokely Carmichael. And this is not, and I would argue, personally, my own bias, that a woman like Claudia Hampton would not have been successful, were it not for a more militant Black civil rights movement, which even included Martin Luther King and others, if you can use that word, militant and taking it outside of the major institutions, challenging and so forth. But nonetheless, I’m persuaded by this book, and I think it’s an important contribution to the scholarship of the issue about the effectiveness of a certain notion of soft power, which is called in the book ‘sly civility,’ and what it basically argues. And this woman is the champion that’s offered, Claudia Hampton, of people who used the system, played the game of the system, but didn’t sell out, and they were now, one could argue whether that also applies to Barack Obama or Kamala Harris or others that are, particularly Kamala Harris is now in the news, and this has nothing to do with the main subject of the book, which is affirmative action. These are not by any stretch of the imagination, affirmative action children, whatever that might mean. These are people who came from a solid background of economic and educational achievement and would have succeeded, probably, no matter whether you had affirmative action or not, but, and in fact, Claudia Hampton was appointed to be a trustee of the Cal State system by Ronald Reagan. And even when he was governor, and even when he was president, he actually appointed her to another commission and so forth. So she has really respectable trends. In fact, there’s a phrase used in this book by Bucha. I should say it was published by the University of Rochester press. And there’s a statement in your notion of respectability politics. So I’m going to turn it over to you. And we do want to talk about what happened to affirmative action, which effectively was killed by Supreme Court decisions and so forth. I personally think it should be a non-controversial notion. I teach at a school that is still USC, primarily white and primarily people who have come from a background of considerable privilege. I think you could argue that about UCLA across town, even though it’s a public institution. I think the statistics on participation from underrepresented groups are appalling and so forth. So I personally put it right out there. I have no question that we need affirmative action of every kind, and class based, racially informed, or whatever, to include the people who are not included in society and to the best of their ability. But I’m going to let you lay out why this research, how your own educational background contributes to it, and talk about, here we are in this great blue state, and I, frankly, don’t think we’ve done a great job in terms of representation of people. I’ll throw one little zinger at you I was going to say to the end, are we really doing people a great favor when we bring them into a structure of education where, if you don’t go to the Ivy League schools and the top privileged places and so forth, maybe it wasn’t even worth the trip. We don’t know. That’s an argument you hear from time to time. So I’m going to promise I won’t talk this much. I’ve talked way too much. Take it over.

Nickel: All right, well thank you so much for having me. I really appreciate the interest in the book and that you have read the book. When I started out with this project, it was to get an understanding of how the trustees in the Cal State system worked. Because even though I got my bachelor’s degree and my master’s degree at a Cal State, and I worked as a faculty member for 20 years in the Cal State system, I still didn’t understand how much power the trustees, the Board of Governors, the Board of Regents, how much power they had behind all types of decisions, whether it’s personnel decisions, whether it’s the funding the student newspaper, all the way to hiring the chancellor. So understanding that was one of my goals of the project. But another part was how I discovered this woman was by happenstance. Claudia Hampton, as you say, was the first black woman trustee in the Cal State system. She was appointed by Ronald Reagan in 1974 and she became the first woman to ever chair the board in 1979 and really I discovered her when I saw a photograph of her in a digital archive looking up information about an organization that my grandmother created called the Office for Black Community Development. I just stumbled across this picture and it said at the bottom of the photo, ‘appointed by Ronald Reagan.’ And I said, ‘Wait a minute, Ronald Reagan,’ this struck me as really odd, because knowing what I thought I knew about Reagan and his relationship to race, and his record on civil rights, I was a little floored by this, so I went and googled her and saw that, yeah, she was in fact, a trustee. But I didn’t see much else written about her or anything like that, until I physically went into the archive and saw that someone had recorded a six hour interview with her, and it was at the bottom of a box. And so I decided to transcribe it. And once I transcribed that interview, I knew I had to do something with this information. I had to let people know that there was this woman who had been appointed by Reagan and served on this board. I started to go through the Cal State archives to look for anything that I could find about her, and there actually was a treasure trove of things there. No one actually had gone through that archive except for me, I’m told by the archivist. I was one of the first because the Cal States, for some reason, as big of a system as it is, with 23 campuses, we tend to only pay attention to the UCs and the private institutions in California, and the Cal States kind of occupy a second tier. And there’s a reason for that, and I write about this in this history that the UCs were protected by the state constitution as a public trust, which means that the public would trust the universities to govern themselves, and in exchange, or not in exchange, but in addition, the state will fund the the UCs. The Cal States, on the other hand, were created after the gold rush through a statutory provision in order to create a class of teachers to help educate the children of the people who came over with the gold rush. So that second tier meant that the Cal States were always dependent on not only the state for money, but also the State Board of Education for governance and control. And so again, I really just part of it was a curiosity of understanding how the system worked. But Claudia Hampton is coming at a time when Black radicalism becomes very popular after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., and you see the rise of the Black Panther Party and other more left leaning groups. And she’s working in the system as not as a Black radical, but as someone who chooses a different way of operating, a different way of leading, which I refer to in the book as Sly Civility, and that is because she understands that her race and her gender are things that can be held against her. And she’s not the first Black trustee. She is the first Black woman trustee. There was a Black man named Edward Lee, but he didn’t really do much because he didn’t sit on the board as long as she did. But Hampton figures out pretty quickly that in order for her to be effective, she’s going to have to build relationships with the majority white men, more conservative leaning white men who were Reagan appointees and Pat Brown appointees. She also came from the LA Unified School District, and that factors in quite a bit to her story, because she was responsible for the desegregation efforts of the LA Unified School District from the office called the Office for Schools and Community Relations. It was created after the Watts riots, and it was a McComb commission recommendation to go in and triage race flare ups throughout the school district. So before she even got onto the board of trustees, she had a lot of experience dealing with different race conflict and cultural conflict, and so she brought all of that to her work on the board of trustees.

Scheer: But really, let’s cut to the chase here, the radicals that you referred to, and that would include, for instance, Angela Davis, who was, I think, at UC San Diego at that time, and others would probably have dismissed her without investigating that much as part of the problem, and maybe even a hack or so. Not uniformly, because there were supportive faculty and others in the university and state college system, but generally, selling out was a big notion, I still think, a very important notion. How do we keep our integrity in relation to power, wealth, success and so forth? How do you get appointed by Ronald Reagan, and what were his expectations? And are you going to continue to be functioning? Then, amazingly enough, Reagan gets to be president. He points her to another important position. And by the way, I interviewed Reagan before he was governor and when he was governor, before he became president, and I always felt he shouldn’t be dismissed as simply one thing or another. Reagan had a fairly complex life, born in the depression and so forth, and had mixed feelings, and certainly would have taken umbrage at being considered a racist if one could argue about his practice, but he certainly would get hot under the collar that were suggested and tell you all the reasons why he’s not so why don’t we cut to the chase here? Because what your book really, why it’s so important, is to maybe help people like myself understand other role models. That’s really the power of this book for me, reading it, it was kind of a self correction. Maybe this is someone I would have dismissed. My life was more activist, maybe. So I want you to make that argument that the book makes, that this woman was the opposite of a sellout, that she actually accomplished a great deal because she figured out how to work in the system. And hopefully, with someone like, say, Kamala Harris is very much in the news, that’s the question, What role will she play? And we don’t want her to simply type people, if they were successful, they can’t have a soul. We’re seeing now two sides of Kamala Harris. In some sense, when she talked about the people in Gaza suffering, as she did at the Selma march, as she did after meeting with Netanyahu, we saw some of that spirit there. There are universal civil rights that have to be respected. On the other hand, she’s been part of an administration where she seems to go along with stuff that sometimes contradicts that. So help me understand the role of a Black woman in these situations, and how and the point of view of the book, which is, I think, a major study in this respect, that cuts through different sorts of stereotypes and two obvious observations.

Nickel: Yeah, so thank you for that question. Claudia Hampton provides an example of someone who understands that in order to help her people, she’s very explicit about wanting to help Black students, low income students, women. She’s very explicit about that, but she knows that what she’s up against is, you know, men who practice this kind of blunt power, that she has to figure out, ‘I need to use some soft power in order to make headwind’ and so sly civility offers her that possibility without her losing her connection to her community. She stays, she lives in a Black community. She stays connected to the organizations that she belongs to, her church, her sorority, her political action committee that she created. In many ways, she’s functioning like Shirley Chisholm, someone who says that, ‘yes, I’m in Congress, I’m fighting, I’m not selling out, I’m trying to provide resources to you. You need somebody on the inside, even though you’re agitating on the outside, and that’s fine.’ We need that agitation on the outside, but we need somebody on the inside to translate this into policy, to translate this into resources for the community. And so Hampton, what she does is, the way in which Hampton functions is she’s not demonizing the radical left. She’s actually trying to make their desires and concerns heard, but in a way that’s palatable to people who would dismiss them out of hand. I think she offers a real opportunity for us to say that there are multiple approaches, and that the radical left, if you want to call it that, and this moderate, this Black pragmatist, can work together. No one had ever accused her of being a sellout to the community because she was constantly getting resources back out. So affirmative action languished in California, in the Cal State system without her kind of pushing them, particularly when it came to financing affirmative action programs. During her 20 years on the board, you see the highest increase of students of color, of faculty of color, and those numbers have not been replicated since then, so she may have caught some flack from people who didn’t understand that you can have a both end approach to leadership, as opposed to an either/ or.

Scheer: Yeah, I think that’s critical. We haven’t really talked about affirmative action. And you know, I just want to put my own bias, if that’s it, or my own conclusion. I don’t think we’ve had enough of it. And I also don’t accept the argument that it shouldn’t extend to people who are more privileged economically or so forth, because they will meet barriers. I can tell you right at USC currently, I can give you the names of some colleagues that have not been appreciated as fully as they should because they had different emphasis, or what have you. And obviously it applies to women as a category, so why don’t you talk about that? Because you’re really, you’re making a strenuous argument for needing to tip the scale. Let’s put it crudely, the scale is unequal. It’s not working, right? You have to tip it. Why don’t you take your argument, which runs right through the book?

Nickel: I really try to trace that narrative, or the historical arc of affirmative action. There’s two parallel stories that are kind of happening in the book. You have what is happening at the national level and the state level, and then you have what’s happening in the Cal State system, kind of happening all at the same time. And the reason why you need someone like Claudia Hampton is because the implementation of affirmative action is the challenge. Getting it on paper was relatively easy, implementing it was another story. There were constant barriers. There was all this slow walking affirmative action, either they wouldn’t fund it. You had people who were supposed to be supposedly champions of affirmative action. Jerry Brown, who never wanted to fund affirmative action, didn’t see it as politically sexy. He would fund EOP, the Educational Opportunity Program, like the pre college programs, but he would never fund affirmative action until he started to get pressure from the California Faculty Association. And you really need affirmative action, because if left to people’s own devices, they would not include diversity in the universities. In fact, one of the problems after affirmative action was created in 65 by Johnson is that there were no rules for how to implement affirmative action, until a group of feminists started to press the federal government. And so what was happening was that universities would say, ‘well, we’re committed to non discrimination.’ And they thought that that was enough just saying, ‘Oh, we won’t bar someone from coming in because they’re a woman or because they are immigrants’. That’s not enough. Affirmative action says you have to go out and actively recruit these people to ensure diversity within the classroom. And so there was a lot of attempts to sidestep the law, whether it was in California or elsewhere, and you see, just to, you know, to put a fine point on the material consequence of losing affirmative action in the city of Los Angeles, African Americans represented 15% of all city contracts before affirmative action was ended. After affirmative action and currently, African Americans only hold 0.23% of all government contracts. So there is something to be said about having the law to make sure that people consider all different groups of people for these opportunities.

Scheer: So how did it get knocked out?

Nickel: It got knocked out because there was a coalescing of a whole lot of things happening. You have the economic recession, and that tends to bring out this kind of hyper racism. That is one part of it. You have Proposition 187 which is the Save Our State Referendum, which is basically to not give any services to undocumented immigrants that Pete Wilson latched on to in order to save his gubernatorial campaign. You have the LA riots in 1992 for Rodney King. And then you also have this kind of concerted media attacks, which is funded by conservative philanthropic dollars. So you have a lot of things like the welfare queen and all of these kinds of racial dog whistles. So all of these things are coming together. And so there’s an appetite to get rid of affirmative action, because it’s like, ‘Well, look, if those people that live in LA that’s tearing up their own neighborhood and tearing up property, they don’t need affirmative action. Why should they get more opportunity than the rest of us,’ but in actuality —

Scheer: The prison system, that was the thing, yeah, but let me push back a little bit on this, because it’s interesting. Pete Wilson, who, you mentioned prop 187 which actually concerns the Brown community more than the Black community. But when Pete Wilson came in, Republicans generally believed in, well, they were more moderate, and they believed in more open borders. They believed in not punishing people, after all, they’re trying to work. He even went for something at one point, the tip program, which they protected the rights of undocumented workers even if they didn’t have papers, they still had the right to working conditions and so and then he did a flip flop, and he did it, as you mentioned, accurately, to get reelected in a changing tie. And now the Republicans are associated more with meanness, and so I want to take this figure of Reagan and the person you were writing about. Did Reagan ever discuss why he appointed Claudia Hampton, this clearly reformer, clearly someone who believed in affirmative action? Did he address that?

Nickel: Well, it really comes up in Claudia Hampton’s relationship with Reagan’s Education Secretary, a man by the name of Alex Sheriffs. And so there was a chance meeting between Sheriffs and Hampton, and Sheriffs kind of informally vetted Claudia Hampton to try to find out what her race politics were, because Sheriffs knew he was about to be appointed as the Vice Chancellor of Academic Affairs for the Cal State system, and so he went into Reagan’s office after about a year of vetting Claudia Hampton and saying, you know, would you appoint her? Because I need a friendly face on the board, someone that, you know, I could kind of rely on to kind of have my back, is kind of the language that Sheriff uses. And so Reagan is like, well, who is she? And so he says, oh, you know, I’ve been meeting with this NAACP group, and I’ve kind of whittled it down from 12 people from their initial meeting down to Claudia Hampton. And so she went and met with Reagan. They had one conversation. She says it was about cultural things. And so Reagan made the appointment really based on the strength of her relationship to Alex Sheriffs. What’s interesting about the appointment is that one, Hampton, was a Democrat. Hampton was also part of the NAACP, which Reagan had basically dismissed as almost like a terrorist organization in so many words, and then she actively had a political action group that helped to elect Democratic candidates. So it just seemed like it didn’t seem to fit this persona or understanding of Reagan. But it was again, because the relationships she built and people got to know her as a moderate, that’s how Reagan appointed her to a federal commission on education because he found out more about her educational background in the LA Unified School District, as well as her work on the trustee board.

Scheer: You know, it’s interesting because I got to meet Reagan only because he had a Black journalist from the San Francisco Examiner working as his press person when he was first running. I’m not going to quote him or anything, but this person really thought that Reagan wanted, that he didn’t believe Reagan did not believe he was a racist, okay, it just offended him deeply, that idea, and he said, ‘Wait a minute, I played ball with these, with people. I came up this way, I came up that way.’ I remember his face would get red if you tried to push that line. I’m not speaking out of any naivete. I was tear gassed by Reagan when he sent the helicopters over Berkeley. I was a graduate student there then. I know the downside of Ronald Reagan, but the man genuinely believed that he was anti racist. So the whole argument about affirmative action stumbles over the question of meritocracy and fairness, like the Bucha decision, which we haven’t talked about. Why shouldn’t this young, hard working fellow get into Cal when other people can. And it hit me all this time and again, I promise I wouldn’t talk so much, but I’ve lived through a lot of this. I went to City College in New York where, you know, that was fed by something very much like the California master plan for education. And they had in common that basically every group in society should be given a serious avenue to power. This will how you’ll make democracy work, and education is the key. So again, like in California, New York State had the state college system. If you couldn’t get into the City University, when you get to an equivalent of a junior college or something, the California Master Plan went further than I think anybody else in that respect. These were not supposed to be terminal, meaningless degrees or just vocational education. The master plan actually saw the community college getting you even to the most elite schools, UC and so forth. And it wasn’t working, I would ask you, you’re an expert on education, it seems to me, because the lower levels of education were not working, the schools were not equal. Yeah, I mean, so why don’t we go there? Start with the four year old preschooler and the situation, rather than talk about who at the end of the road should get in after having gone to the better high school, even public high school or private high school, and then, ‘Oh yeah, I should have an equal opportunity to get ahead at Cal,’ but we really go back to the earlier problem.

Nickel: Yeah, so the earliest, and Hampton was actually instrumental in working on these issues when she was in the LA Unified School District, that you had so many schools that were poorly resourced, that were poorly staffed. You had so many challenges at the at the K 12 level that it would make it difficult for a student to get into the Cal States or the UCs, but the question becomes what kind of programs or services are you offering to make up for whatever those deficiencies might be, and part of affirmative action is to have these pre college programs that would help those students, low income students in particular, who found themselves in these schools that did not have the extra drama program, or the other co curricular programs that would make this student better equipped in order to get into the UCs or the Cal States. And so a lot of what was happening, though, is that you would have a number of Trustee members who would say, ‘Well the problem is the K 12 system. We can’t help that the K 12 system is poorly funded or not doing well,’ and use that as the reason to not admit students of color and other low income students. And so the California Master Plan does provide an opportunity for everyone in the state to get an education. But this is the thing about the master plan, it diverted most of the students to the community colleges, and most of the students that they diverted were Black and Brown and and non white students, and so they reserved one quarter of admission, for the UCs, 1/3 of admissions will go to the community colleges. And the majority of students went to the community colleges, not because these students were poorly prepared, but because it was cheaper to educate students in the community colleges. And the problem with our community college system, even to this day, is that transfer rates from the community colleges to the four year institutions is still very low. And so what is happening? Why don’t these students continue on and finish their degree? Part of it, even now, especially now that we got rid of affirmative action in California, is that we don’t have the support programs that we used to have. The Educational Opportunity Program. You can only be eligible for EOP in the Cal State system if your family can only contribute no more than $1,500 to your education. So if anyone is not in abject poverty, you don’t get any of the tutoring programs and all of the advising support that would normally support these students. So there’s some structural problems with the K-12 education and even our current support systems, and so to get rid of affirmative action in the midst of all of these structural issues is just the messaging that we don’t want certain groups of students in our universities.

Scheer: Yeah, and it’s appalling, because the fact is, everybody benefits at some point in their life from extra help. May it come from the family, it may come from private tutoring, and may come from being able to go to certain specialized schools. And since we mentioned USC before, Claudia Hampton is getting her doctorate there. You cannot go to a frontline school like USC, which has a big athletic program, and not recognize some contradictions. And we had, I think her name was Dr. Edie in the Education Department. I met her, I think once or twice, but she said, we have these NCAA rules for athletes, and you’re violating the regulations if you don’t make them available to everybody, including incoming students, meaning you can come in, but you didn’t fully qualify because you were weak in this or that, or you have a learning disability, you have a gap, but you can come and go here for a year, and then if you fulfill these requirements and show you can learn in a different way, then we go, and I think it’s the most successful program at a place like USC. It may be many other schools. Because there’s a need. We want athletes, so therefore, it turns out, you can help people get up to speed who are not well served by their earlier education. And I just remember when I encountered this, and now that I teach there, I’ve seen that it works, but no one wants to ever acknowledge that the extra help like we have to we now are required by law and Bob Dole, a Republican senator who was so instrumental because he himself had been wounded in the war and believed in the Disabilities Act. But the fact of the matter is, it is fixable. And what I think the lesson of Claudia Hampton and the book is published by University of Rochester Press. We’re going to be wrapping this up, but I want people to look at it, because it’s a great success story. And what she was able to do was say, ‘Okay, you say this and you say that, and this doesn’t work and that doesn’t work, and I’m going to show you how to make it work.’ And really, the message of the book is, if the will is there, meaning these are not throw away children or throw away students or throw away populations, but they are people with equal potential, right? And you know, there’s some idea you have in the book of any group, you have your top 15% of really superior potential. I forget the way you put it, but yes, I mean, there is tracking within groups. We all have different skills and different things, but you want to be able to provide this opportunity at every level, and really what you turn on. One thing that’s not mentioned enough is the economic disadvantage, which, of course, applies to poor whites as well. What you really want to do for these people of any color is provide what the society failed to provide and what their family couldn’t provide and their wealth status couldn’t provide, and that’s what got obliterated on the attack on affirmative action, and really was a great setback. And I think what you said about Jerry Brown is very disappointing, because he certainly came from a privileged position, and certainly to become the governor, and having your father be a very successful governor until he wasn’t is a good example. So what she was able to do, it seems to me, is what these more militant people wanted to do, which cut through the BS and, you know, talk about how the system really works. But she used something that I don’t have a lot of respect for, but perhaps I should have more respect for. She used this soft power, we have a whole big soft power unit at USC and I, and reading your book made me think, well, you know, yeah, not everybody should be out demonstrating. There are people who can use the question, because I promised it to people listening that we get to it take a few more minutes, if you have the time. How does this apply to somebody like Kamala Harris, and let you take the remaining time, as you will, to see if it does apply?

Nickel: Yeah, I really think that you can draw a line between the campus and the Capitol. And the way in which to think about this is that a lot of the strategies that Claudia Hampton had to use, which were strategies of influencing people to change or to change the institution from inside, is something that you will you will see, or you can see in Kamala Harris, just the narrative device of the code switching that she does, that she’s speaking to different audiences at different times, in different ways. Claudia Hampton did a lot of that because she had to, she cooked dinner for these white men, which, you know, I was raised in a Black radical tradition so that seemed foreign to me, but she knew that in order to make deals with them, she had to be on the inside of their decision making, and so one of the ways she spoke to them is by playing to the gender norm, as in, to disarm their racism. In a lot of ways, you can see that Kamala Harris has to speak to different audiences at different moments. Just a few days ago, when she was at the rally, and she was dealing with the pro Palestinian folks who were in the audience, who were talking when she was talking, and the way she took this kind of stance, in one instance, you see people who are really upset that she’s dismissive of the pro Palestinian stance and what’s happening in Gaza. But then there were other people who were applauding her for the kind of strength that she was utilizing. And it’s a juggling act. Claudia Hampton had to do that same kind of juggling act of this is what my constituents, the people, my supporters, want. But I have these men and these policy makers who are in opposition, and how do I find a happy medium? And so when you are, in this case, when you’re a Black woman, because you have to deal with racism and sexism, you’re going to have to figure out some kind of way to get people to not focus so much on your identity, but what you actually bring to the table, and that’s hard for a lot of Americans to do, because we’ve been socialized to see race and gender as immutable characteristics that you can’t get past. And so I see a direct line, and then there’s this kind of lineage of Black women who have done this in political office. Mary McLeod Bethune could not have walked into the Black cabinet with Roosevelt and said, ‘Look, we demand this, this, this, and this.’ She had to use some strategies, I’m sure, that would say, ‘Okay, Mr. President, I agree with you on this, but I disagree with you on that,’ and so you can’t just assume that the righteousness or the morality of your cause is enough. You have to build relationships with people, and that’s what Hampton does.

Scheer: So in your book, it’s a good way to end this, but you say sly civility and respectability as resistance. When can it be co-option? And let me take it away from race and talk more about gender as another category. Was Hillary Clinton engaged in sly civility and resistance talking to white men, or did she sell out any consciousness she had? I don’t want to put you on the spot with a specific person, but that is the question. At the end of his life, Martin Luther King was certainly broke with his father’s model, and he listened to more radical people, but was a moderate, was close to Lyndon Johnson, and his administration, had a lot of support for Bobby Kennedy, but the end of the day, they sic the FBI on him and tried to destroy him and everything else. And Martin Luther King now resurrected as a very establishment, respectable figure, was alienated, was a radical, and called his own government the major purveyor of violence in the world today. And was supporting a poor people’s march because he said poverty is the great cause of the downtrodden, ultimately, and he was going to do something about it. So I’m just wondering, because I respect what your book does, it forces someone like myself to think and challenge my own bias in the situation. But how would you answer that?

Nickel: So with regard to Hillary Clinton, I think one of the, and it’s funny you bring this up, because when I taught my women in leadership class, I had my students do a case study on Hillary Clinton versus Pelosi in terms of their leadership styles. And I said, ‘You know what? What is coming up for you in terms of differences?’ And they said, ‘Well, you know, Hillary Clinton comes into the White House as the first lady. She is going after the HMOs. She seems really committed to this idea of universal health care. But when it’s time, when she gets the backlash against that and she wants to be electable in New York, she switches and takes money from the HMOs.’ And I was like, ‘Yeah, okay, yep, that’s fair.’ And so then I said, ‘Well, what? What about Nancy Pelosi?’ And they said, ‘It just seems like she chipped away, like she worked her way to the top, as opposed to using her husband or her father’s name to get into her position. You know, she did it on her own merit.’ And so what I find is that sly civility can be used by anybody. So it’s not restricted to just Black women, but the use of it requires you to not only be strategic, but to have a kind of vision for who you’re going to help from it. It can’t be just about helping yourself. Sly civility is really about ‘I’ve come into this place, I’m going to be the instrument of change in order to help a particular group.’ And so I think that’s why Hampton did so well, and she stayed connected to the community, because the further you move away from the community and you’re not engaged in the culture, it’s easy for you to lose sight of who you’re there for. Any newspaper articles that I saw of her in the Los Angeles Sentinel newspaper, because the LA Times didn’t really focus on her, but in the Sentinel, she’s always talking about her responsibility to the community.

Scheer: I worked at the LA Times for 20 years. I never heard of her. Why didn’t they focus on her?

Nickel: I’m not sure. I think it’s a combination of the CSU is just not that popular in the state, even though it educates half a million students a year.

Scheer: Well, let me stop you right there, because that’s also when I was reading your book thinking about that. There’s an illusion about mass education, that it’s really a ladder up. It may also be a great deception. And you know what? Maybe, no, I’m not speaking disrespectfully to say I was at the last graduation at Cal State LA, and it was very impressive to see all the people there and the speeches and the families and all that. But then you wonder, what jobs are really awaiting? Now they’re always exceptional people. But in fact, is this a way of side tracking people? And then let’s end this interview with the sad statistics that we have a huge prison population. We have at USC, the place where she got her doctorate. We have almost these daily reports about crime, and they involve a five foot 10 Hispanic person, a six foot one African American or Black person they had described. Now our police department, our private police department, the city policemen, are racially integrated to a considerable degree. Some battles are being won, but the results and the absence of any serious affirmative action are atrocious. We are in a racially divided society of a degree that we haven’t even seen. And not only that, the class divided. Class, whites, poor whites, and we have a disappearing middle class. I mean, it’s astounding what we’ve accepted as the new normal, and taking your point, which I think is so good. I interviewed Bill Clinton before he was President, and I got to know him, and even got invited to a White House dinner. Both he and Hillary Clinton were very nice, but the fact the matter is, he didn’t do what Claudia Hampton did. He didn’t stay with the poor whites of Arkansas. Forget about the black people he came to care about. He just forgot about him. He ran with the rich. He ran with the elite, you know. And he bought the Yale idea, and so did Hillary. She basically abandoned the drugstore owners’ circle and so forth, and ‘but no, I’m in the elite now,’ the Rhodes Scholar elite that Bill Clinton was in. Maybe you could just say a few words about that, because you actually represented a very successful person as well as the person you wrote about. And you must get depressed sometimes, counseling students or talking to them, and you know what is really in the offering for them? And was this education really meaningful? Is it a way out?

Nickel: That’s a great question. I will say this about Claudia Hampton, I mentioned in the book there are a number of ways to be socialized in society. And you know, you got the micro level, the mezzo level, and the macro level. And the mezzo level is the one that doesn’t get talked about a lot, and that’s that community level where you what can you do to help your immediate community, and there is a type of leadership called developmental leadership that black women have been engaged in. Valency calls it a tradition that has no name, where you’re organizing for community success, and you’re using whatever gifts and talents that you have in order to help your community, to kind of give back, and that’s a big part of the kind of cultural thrust in within African American families. And so I think that Hampton really took that part to heart. So it’s not her individual success that’s meaningful, even though, individually, she was well accomplished on her own. But that, what could she, what does Toni Morrison say? Freedom means that you need to free someone else. And so how do you use your gifts and your talents to help other people get free. I think Hampton took that to heart, whereas someone like Clinton, and there’s nothing wrong with being ambitious. So let me be clear. I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with being ambitious, but the problem is, when you are being ambitious and you’re steamrolling over people in the process to get to whatever that goal is, or you’re forgetting the people you initially tried to build your bona fides with. That can be a problem. So I mean, I think about Hillary Clinton, when she worked as a corporate attorney, and how she defended corporations over individual people. So maybe there was something early on that told her it’s okay as long as I’m doing my job. Whereas Hampton, I believe she felt like this was a calling and a responsibility. So I think that’s the difference between them. But in terms of working with young people and trying to give them hope even when the job prospects are not that great, I don’t approach education necessarily from the prospect of workforce development and when you get a job. I tell the students, I am here to incite you. I’m not here to create a safe space for you. I’m here to get you to think more creatively and critically. So maybe you don’t get a traditional job, whatever that might be, maybe you make a job that’s based on your passion and things that resonate with you. Now, that sounds a little lofty, or whatever. You know, folks gotta eat, so I understand that part too.

Scheer: But they’re not going to eat drinking the Kool Aid anyway. Yeah, okay, ‘Shun that and shun that,’ then the jobs aren’t necessarily there. And in fact, as we see with people who go into, say, rap music, or they go into other things, you can make your own job. I mean, you know, force it. But I want to say what you just said to me was worth the whole effort, because you’re challenging a now dominant notion that creating safe space is the essence of fairness and equality and education, rather than critical thinking challenge and so forth. And I haven’t heard anyone put it quite the way you just put it. But I feel, as a professor, that is the intimidating thing, what we can’t talk about, and sometimes it’s defended in political correctness but the safe environment. I’d rather in my class have a spirited discussion about affirmative action where people really open up and do critical thinking, and you really put that as the goal, we create a safe space. But for what? Reality is not safe. Society is not safe. Okay, well, that is a reason to buy this book, which the title I’ve now misplaced. Yes, Black Woman on Board. We’re talking about a specific woman. We’re talking about Claudia Hampton, who did get her doctorate at USC in 1970. Go Trojans, not putting down the whole institution. University of Rochester Press. And I want to say you may think, ‘Well, what has this got to do with me? I’m not going to community college or so what and everything.’ It’s really the counter narrative about affirmative action, why people fought for it, what you can do within the system. It gives to my mind a more profound meaning to soft power, which I often think is just an excuse for more effective propaganda and so forth, just to be honest. But now I’m becoming something of a convert, at least being open minded about it. Some of my colleagues really believe in it. It’s written by Dr. Donna J. Nickel, Associate Dean of Curriculum, Professor of History at Cal State University, and I do want to say something, as somebody who’s grown up, not grown up. I came to Berkeley as a graduate student after New York, but I’ve spent 50 years in California. I’ve spoken in a lot of schools, and I really do admire the community colleges, and I definitely admire the state colleges very much. And when I’ve spoken at that and I think and they these people. Really work hard. That’s where you do four or five classes, and sometimes whip together, and they don’t have great tenure protection and everything, but I think it’s the saving grace of American education. And I’m paying back my debt to City College in New York. And so there. Thanks for doing this, and let me thank the people who put this all together. I got my cheat sheets here. I want to thank Christopher Ho and Laura Kondourajian at KCRW for posting these shows. I think it’s a very good NPR station, and does a lot of good work. Joshua Scheer, our executive producer, who really educated me about this book, Diego Ramos, who writes the introduction, Max Jones, who puts it all together with video and everything else. The JKW Foundation in memory of very good writer, Jean Stein, who cared a lot about these issues and Integrity Media out of Chicago, which cares a lot about social justice and journalism. See you next week with another edition of Scheer Intelligence.

Please share this story and help us grow our network!

Robert Scheer

Robert Scheer, publisher of ScheerPost and award-winning journalist and author of a dozen books, has a reputation for strong social and political writing over his nearly 60 years as a journalist. His award-winning journalism has appeared in publications nationwide—he was Vietnam correspondent and editor of Ramparts magazine, national correspondent and columnist for the Los Angeles Times—and his in-depth interviews with Jimmy Carter, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, Mikhail Gorbachev and others made headlines. He co-hosted KCRW’s political program Left, Right and Center and now hosts Scheer Intelligence, an independent ScheerPost podcast with people who discuss the day’s most important issues.

Editor’s Note: At a moment when the once vaunted model of responsible journalism is overwhelmingly the play thing of self-serving billionaires and their corporate scribes, alternatives of integrity are desperately needed, and ScheerPost is one of them. Please support our independent journalism by contributing to our online donation platform, Network for Good, or send a check to our new PO Box. We can’t thank you enough, and promise to keep bringing you this kind of vital news.

You can also make a donation to our PayPal or subscribe to our Patreon.