Click to subscribe on: Apple / Spotify / Google Play/ Amazon / YouTube / Rumble

In the midst of the ongoing destruction of Gaza and the slaughter of Palestinians, the identity and authenticity of Jewish people calling into question the actions of Israel are being tarnished. A greater discussion of what it means to be Jewish, what it means to have a Jewish state and what Judaism has historically taught people is taking place among Jews around the world.

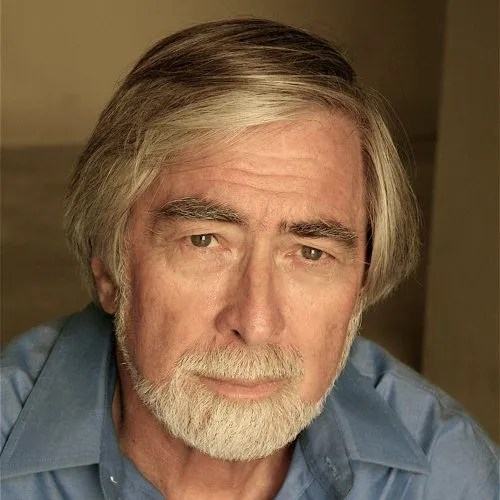

On this episode of the Scheer Intelligence podcast, Heyday Books publisher and former LA Times book editor Steve Wasserman and host Robert Scheer commit themselves to this conversation as Jews who have experienced these questions firsthand through their families in addition to having explored and reported on this topic throughout their careers.

Whether it was through Scheer’s reporting (with research by a youthful Wassernan) on the “Jews of L.A.” series for the Los Angeles Times and his reporting on the Six Day War in Israel and Gaza or Wasserman’s work with authors exploring Zionism and Israel, the pair have dealt in depth with the issue at hand.

Both stress the importance of Jewish culture in shaping their upbringing and viewing the world from a progressive, inclusive lens. Wasserman explains that for him Judaism encapsulates “The idea of being an honorable, ethical person, about making the world better, performing tikkun, helping to heal the world.”

As it pertains to his own familial history, Wasserman explains his mother’s brothers’ sacrifice: “They were premature anti-fascist. And they were eager to fight Hitler. And, they were killed within a week of each other… My mother has never gotten over their sacrifice. So, yes, we shed blood in the war against fascism.”

While delving into the idea of Israel, the two acknowledge the complexities of the history as it relates to the struggles of the diaspora and the Holocaust, but still, Wasserman acknowledges, “I’ve never thought that Israel or the State of Israel spoke for everyone. I’m a disciple of I.F. Stone, who said that all governments lie, including governments that you might be attached to for emotional and historical reasons.”

You can also make a donation to our PayPal or subscribe to our Patreon.

Credits

Host:

Producer:

Introduction:

Transcript

This transcript was produced by an automated transcription service. Please refer to the audio interview to ensure accuracy.

Robert Scheer: Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of Scheer Intelligence where the intelligence comes from my guest and in this case, someone I knew from when he was a high school student in Berkeley, California. His name is Steve Wasserman. He didn’t write or edit all the books behind him in the picture, if you’re looking at the video version of this conversation. But he is in his office at Heyday Books in Berkeley, a remarkable organization made even more important by Steve, since becoming its publisher in 2016. He’s been a major editor for a variety of publishing houses for many decades. Tell us about your career, Steve, and your relation to those books behind you.

Steve Wasserman: What can I say? I’m a mad and obsessed reader. The more I read, the less I know. I hope that my brain resembles something like a colander where the grid is so finely woven together that, as I pour, knowledge like sand through the weave, enough collects on the grid that I retain and hopefully, prompts me to further exploration. But first I should tell how I began to work with Bob Scheer. I was in my senior year at UC Berkeley, and I was seeing a woman who lived in the house that he lived in, in Berkeley, and his then girlfriend, and we all went to have a Chinese meal at the Yen Ching in Chinatown in San Francisco. And we went to see Chrissy Everett and Billie Jean King play the Virginia Slims tennis tournament. We came back to Berkeley and we played chess, and we smoked a couple of cigars. I went home and at eight in the morning, Bob calls me to say, I’m trying to work on this book, I’m under contract for a book about multinational corporations, and maybe we could have coffee and we could talk about it, and maybe you could become a researcher for me.

And so we began a long association. I had, eight years before, worked as a kind of foot soldier in his campaign, when Bob ran for Congress in 1966, in the seventh Congressional district here in Berkeley, to try to unseat Jeffrey Cohelan, who was the Democratic representative and an apologist for Johnson’s war in Vietnam. Bob ran against him on a two-pronged platform to end the war in Vietnam and end poverty in Oakland. He lost but garnered 45 percent of the vote. Two years later, Ronald Dellums won the seat and remained in Congress for the next forty years. Eight years later, Bob and I began to work on that book, which would be published in the fall of 1974 under the title “America After Nixon: The Age of the Multinationals.” It was one of the early explorations of a phenomenon that is now known as globalism, but which we in our spirited dissent called imperialism. I remember being in New York with Bob when that book was about to go to press. It was in the age before computers, and when Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974, it fell to me, the lowly researcher, to go through the page proofs and change all the tenses from the present, as in Nixon is to the past, as in Nixon was. I assure you that no task so tedious was ever so pleasurable.

Scheer: Yes, but Steve this is about you, not me. And, as is supposed to happen in any mentoring, you’re supposed to reject your mentor or at least outgrow your mentor. Okay, so let me take you back to the books behind you. I don’t want the modest Wasserman, I need a little establishment of your significance in American letters. Okay? And you’ve had an illustrious career, basically, as exhibited by those books behind you.

Wasserman: I seem to be someone who’s determined to work every station in the publishing kitchen. So, I have worked in magazines, newspapers, and book publishers. I’m the former deputy editor of the Los Angeles Times opinion section, when they had an opinion section. I’m the former editor of the Los Angeles Times Book Review, when they had a book review. I was publisher and editorial director of an imprint at Farrar, Straus & Giroux called Hill and Wang. I was editorial director of Times Books, when it was an imprint at Random House. I was editor at large at Yale University Press, and then for the last nearly eight years, I’ve been publisher of Heyday Books, an independent nonprofit publisher, founded fifty years ago. This year, 2024, marks our fiftieth anniversary in business. No small achievement for a hardscrabble upstart publisher specializing in California history, issues of social justice, and as Bob mentioned, indigenous native California affairs, and celebrating and defending the environment and nature.

Basically, I have been for the past fifty years the midwife to the birth of ideas of others. It’s been, in some respects, an act of ventriloquism, because even on my best day, I’m always haunted by the conviction that there are others smarter than me, more gifted, who have writerly chops, who have fresher and more original notions. And maybe I can help them shape their arguments, try to find ways to cut through the noise of the culture and get attention for deserving work. That has been the work of the last five decades. That’s the work that I feel passionate about because I’m somebody who believes ideas matter. Books can have an effect out of all proportion to their actual readership. And as they fall through time and circumstance, they gain an authority that only time can bestow.

Scheer: In terms of your description of your relation to writers that you’ve worked with on a very intimate basis, two names jump out: Susan Sontag and Christopher Hitchens. In Hitchens’ case, you had a much more intimate connection with his writing. And I think you should describe that a little bit because it goes to your own independence as a thinker. And I’ve always admired this about you. You were very critical to their thinking. I talked to both of them about your role. I know what I’m talking about. And yet you had your disagreements, and you were, as you said before, committed to getting the debate going, getting the ideas out, even ideas you might not have been totally comfortable with at all times. Is that fair?

Wasserman: Absolutely fair. I met Susan Sontag in April 1974 at a dinner, at your home, on Forest Street in Berkeley. I met her son, my age exactly, David Rieff, who would become a writer in his own right. We’re a month apart. We all became fast friends. Over time, Susan became almost a kind of Auntie Mame figure for me. I spent most of the summer of 1974, while working on your book, living at her penthouse apartment, at 340 Riverside Drive, which had been the painter Jasper Johns’ old studio. I had just graduated from Cal the previous June. She was then living in Paris for the summer. Her son David and I had the run of the place. I remember walking around this sparsely decorated apartment. There was an Eames chair and a few dishes in the cupboards and thousands of books. I nearly got a crick in my neck looking at the titles of all of her books. I had never heard of many of the authors, some I’d heard of but never read. I had just graduated college. I thought, my God, I just wasted four years. My true education begins now. Most engagingly was the clock near her bed, which was a 24-hour world clock that showed time zones across the globe. I thought, my God, this person never sleeps. So intense and deep is her curiosity about the whole world that she’s jealous of the other time zones.

Susan was a very inspiring figure for me. I remember plucking the journals of André Gide off her shelves. There were four blue backed volumes published by Alfred A. Knopf. And for wholly mysterious reasons, I began to read them, feverishly, in the middle of the night. I came across a line that Gide, the great French writer, had confided to his diaries which I never forgot. “I know I will have entered old age,” he wrote, “the moment I awaken in the morning and no longer feel outrage.” I thought that was such a great sentiment—the capacity to be outraged by the way injustice deforms our world. And the notion that if we ever lose the capacity for outrage, we’re finished. Outrage keeps you young.

As for Christopher Hitchens, in October ’79, on my first trip to Europe, I found myself in London. I went to see a fellow named Robin Blackburn, who’d been one of the founding editors and contributors to the New Left Review, founded in 1960, an intellectual journal trying to revivify the Left. I had been very struck by the nature of the contributors and the sophistication of their erudition and their passionate engagement with all kinds of cultures and the way in which they could analyze the economic, cultural, and political circumstances of faraway places and even in their respective home countries.

Blackburn had written several op-ed pieces for me at the Los Angeles Times. So I went to meet him. We got on very well. At one point he looked at me, and said, Are you free for lunch? I know a guy I think you’d get on with. He’s the foreign editor of the New Statesman. His name is Christopher Hitchens. And, he said, I know a very bad Chinese restaurant. We could all meet there. So we did. And the only thing I remember from that meeting was, yes, the potstickers were lousy, but Christopher Hitchens was astonishing. I fell in love. I invited him to write from time to time for the L.A. Times. And thus began a lifelong friendship. I would ultimately introduce him to a woman that became his second wife, Carol Blue. Hey, everyone has agency, so I’m not responsible for what happened with the first wife.

I sent him out on book tour in 1989. I was publishing your collection of essays. I was publishing Jessica Mitford, bringing back into print her great book, “Poison Penmanship: The Gentle Art of Muckraking.” And I was bringing out Christopher Hitchens’ first collection of essays called “Prepared for the Worst.” It occurred to me that I was publishing three generations of a certain kind of muckraking journalist, and we should put you all on the road.

Scheer: Well, that may be the story, but let me just throw my two cents in. As I recall, and I believe, Carol Blue was working with me at the LA Times, and she had replaced you as my researcher.

Wasserman: Yes.

Scheer: At your suggestion.

Wasserman: Yes.

Scheer: You knew this young woman from Berkeley, right? And then, as I recall, you sent her out to the airport to pick up Hitchens.

Wasserman: Yes, he was going to stay with her. Yes, that’s exactly right.

Scheer: But as I recall, at least with the way Hitchens or somebody said this to me, he got back to deliver her to wherever we were supposed to be. And he said, I’ve just met the woman that I’m going to marry. And then you said something like, Christopher, you are married. There was a wrinkle in that. But he said that he instantly fell in love. That’s the story I remember hearing. We also had a big meeting, what is the place famous in L.A. for music, rock and roll, that your sister had access to or she was very involved in the music business, and that was one of the venues where we had our forum.

Wasserman: My sister Rena worked for Bill Graham and was the manager of the Wiltern Theatre.

Scheer: That’s right. And we had our forum at the Wiltern, which I remember suddenly elevated us to rock star status because people were telling me, my God, you’re at the Wiltern. It’s on the marquee.

Wasserman: I think you’re conflating two things.

Scheer: Oh, probably. That’s why I needed you as a researcher.

Wasserman: Yeah. You’re conflating two things. One event with multiple authors was in 1989 to promote your essay collection, Hitchens’ essay collection, and Jessica Mitford’s book. The other was in March of 2003, on the eve of bombs falling on Baghdad, an event at the Wiltern, which Brian Lamb of C-Span broadcast the two-hour debate, which I moderated, featuring you, Mark Danner, Michael Ignatieff, and Christopher Hitchens taking opposing views on the propriety, both morally and politically, ethically and in every other way, regarding American intervention in what Christopher liked to call Mesopotamia.

Scheer: That was a really contentious debate. Danner had written a very important book on torture in the U.S. government, and we were the critics of government policy. Ignatieff and Hitchens were defending going to war in Iraq and defending, basically, in my view, U.S. imperialism. We had profound disagreements about that and several other subjects. The debate encouraged, rather than discouraged, further exploration. Later, when I wrote a book about the military industrial complex, Christopher Hitchens and Carol Blue gave me a party at their apartment in Washington, D.C.

Almost the whole group that was there were the new neoconservative friends of Christopher Hitchens. It was an amazing evening where we’re breaking bread. It’s a nice meal, and I’m in a crowd of people who think I’m the personification of the enemy that’s weakening America. Nonetheless, Hitchens insisted on a civil discussion. It was very enjoyable. We explored the issues. And so I want to pay tribute to you as an intellectual. You always thrilled to the debate. You thrilled to the conversation. I want to get at a quality of the Jewish experience, which, because it’s so much in the news now, and what it means to be a Jew and at some point in life, Christopher Hitchens decided he was also partly Jewish.

Wasserman: No, he didn’t decide. He discovered late in life that his mother, who had committed suicide with her lover, and he was called to identify the bodies in Athens. He only later learned that she was Jewish. This was the family secret. He wrote a profound piece for Ben Sonnenberg, published in the literary quarterly Grand Street, about his discovery of his Jewishness. And that part of the family came from Hamburg. This was a profoundly revelatory experience for him. He was thrilled to learn this because he had always associated that part of the traditions of Jewish people who were attached to the notion of trying to seek the truth, of questioning everything, the intellectual legacy of Spinoza, of not taking things on face value. A dispossessed people, spread in a diaspora who themselves were minorities and oppressed in almost every land they found themselves in, gave the Jews a moral perch, an outsider status that could enrich their critique of both their predicament and engage their empathy with other dispossessed peoples. That legacy was something that was moving to him, and essential to his understanding of himself and his origins.

Scheer: What does it mean to be a Jew? Who speaks for Jews? I think that what you just outlined alludes to an atmosphere. Full disclosure, before I ever met you, I never met your father or mother before, but they came from the same kind of working class, leftist Jewish environment in the Bronx, that I had grown up in. It was a milieu where everything was contended and in fact, in the series we did on the Jews of L.A., involved. And I remember we interviewed Lew Wasserman.

Wasserman: No relation, unfortunately.

Scheer: He was the most powerful person in the film industry at that point. And yet had aroused the ire of some of the official leadership of the Jewish community because he had dared support Jimmy Carter’s peace initiatives. That series, which started out just looking at this community, basically of people like me and your parents, asked important questions. What happened to this whole Jewish experience of criticism, of concern for the other, of social idealism, of cosmopolitan values in the migration from the East to the West Coast? Could we survive prosperity? And we naively asked the question: Is there life after Israel? I can’t speak for you, but I was of the naive view that peace might break out. And we saw later with Clinton that there was a possibility at Oslo and the Camp David Accords that there could be a two-state solution of some kind, an accommodation of two rival nationalisms.

And I daresay Lew Wasserman, probably the most prominent Jewish businessperson in L.A. and a civic leader, could certainly endorse what Carter was doing. And he made a flat-out statement saying, nobody’s going to define being Jewish for me. It was a rather explosive moment. The reason I’m bringing it up is, right now, if you’re a Jewish person, particularly of any political persuasion and whatever you feel about Zionism, you’re under a lot of pressure to think about what that really means. And can the state of Israel really speak for us? Am I being anti-Semitic, or self-hating, if I dare criticize the state? But I want to take you back to a scene because you have such a great literary sense where everybody falls in and I recall a moment at the 92nd Street Y. I had been in Israel and Egypt, and I was in the West Bank right at the end of the Six-Day War. And I remember having a feeling when I had been in Egypt, I identified myself as Jewish and didn’t have any problem.

I talked to some Egyptian Jews who were still in prominent positions. The Six-Day War changed a lot. And then I went over to Israel and I stayed at a kibbutz much like the kibbutz that was attacked viciously by Hamas, made up largely of people who would probably call themselves peaceniks, people who were more on the left, who did believe in trying to find a connection to Palestinians. And I went over to the West Bank and Gaza, and at that time I had this experience in Israel, a feeling of being at home. I felt like I was in New York, but without the anti-Semitism. And I remember feeling that Israel basically was being run by people who all seemed to know Ramparts. The Israelis that I ran into, including very prominent people like Moshe Dayan and Yigal Allon and others representing official Israel, they all considered themselves leftists, believing in some variant of socialism. They all rejected a narrow, jingoistic view. Now, people have since told me I was naive and that my writing about it at that time was naive. Nonetheless, I felt at home with the survival of a certain notion of international Jewish concern for the Other, which, of course showed up in the American civil rights movement, with the important participation of American Jews.

Now, you look at Israel, and it’s a totally different picture, where the more fundamentalist religious believers are a critical and indeed a formal part of the government, supported by very prominent right-wing Jews like the late Sheldon Adelman and others in the United States. I remember that moment at the 92nd Street Y when I had put Ramparts into bankruptcy and I spoke there. And at the end of the talk, an older woman came up to me. I was denounced by quite a few people and yet this woman came up to me and she pointed a finger in my face and said, “You’re right! Don’t let them get to you. Don’t let them frighten you. You are right in everything you said.” That woman was Hannah Arendt.

Wasserman: Really?

Scheer: Yes, it was Hannah Arendt.

Wasserman: Have you ever written of this encounter?

Scheer: I don’t believe I did.

Wasserman: This is the first time I hear this story.

Scheer: Oh, okay.

Wasserman: Never heard the story.

Scheer: So I guess I’m not a good name dropper.

Wasserman: You buried the lede, Bob. You buried the lede for decades.

Scheer: It was very emotional. And, trust me, I needed to hear something like that. I had just put my magazine into bankruptcy. I don’t know if you remember, but a number of our Jewish supporters pulled their money out.

Wasserman: Including Marty Peretz who years later bought and ran The New Republic.

Scheer: It was an incredible moment because I did think that I was speaking out of a Jewish tradition. And that’s why I’m going to bring you back to your parents. Because you were raised, I think, in Oregon, right? Before Berkeley?

Wasserman: My folks left the Bronx, and the block nearby where you grew up and they grew up, in the Coops, the workers cooperative apartments built in 1928 by progressive garment workers. My folks came out west in June of 1952, my mother pregnant with me. My father came out to take a job with the Oregon Highway Department building the road from Mount Hood to Portland. He was a newly minted graduate of Cooper Union, which gave full scholarships. His father was a garment worker and organizer for the Ladies Garment Workers Union, the ILGWU, by day, and by night, he wrote a column in Yiddish for the communist Yiddish paper The Morning Freiheit. And he wrote fiction stories.

Scheer: Did he publish in English or Yiddish?

Wasserman: Yiddish. My father’s first language was Yiddish. He learned English on the playground at six years old when he went to public school. I was born on the West Coast in August 1952. My experience as a Jew is very different from yours. I have never experienced an iota of anti-Semitism or prejudice. We lived for a time in a small hamlet of two thousand people in central Oregon called Madras. We were, to the best of our knowledge, the only Jewish family there. My parents were not religious. There are no rabbis on either side of our family. I come from a long line of atheists, who are proudly, even ardently and fiercely antagonistic to religion of all kinds, but nonetheless have fierce pride in being Jewish. This is something that many non-Jews have difficulty understanding because they associate the notion of being Jewish as they might associate the notion of being Christian, which, to be a Christian, you accept and follow the precepts of Jesus Christ and, bingo, you are a Christian. But the idea of Jewishness is rooted in the DNA. You are born Jewish. Even if you become a practicing Buddhist, you are still a Jew. So what does it mean to be Jewish? This is a question that many Jews have always asked themselves. And for me, in the culture that I grew up, it had something to do with a term in Yiddish called menschlikeit—the idea of being an honorable, ethical person, of making the world better by performing, helping to heal the world. It had more to do with Spinoza than it had to do with Theodor Herzl.

I spent fifteen years encouraging a brilliant writer named Susie Linfield to write a book about the subject of Zionism and its discontents. And finally I acquired her book that Yale University Press published five years ago called “The Lion’s Den: Zionism and the Left from Hannah Arendt to Noam Chomsky.” It examines six exemplary people on the Left and through an examination of their lives and writings, tries to tease out the contradictions and paradoxes of the relationship of the Left as it evolved and developed over the twentieth century with the whole ideology of Zionism, both in theory and in practice. In no particular order, Linfield examines Hannah Arendt, I.F. Stone, the French historian Maxine Robinson, the British New Left Review writer Fred Halliday, Noam Chomsky, and the North African Albert Memmi, who wrote a brilliant book called “The Colonizer and the Colonized.” Susie’s book was relevant five years ago. Circumstances in what Hitchens would have called the Levant and Palestine/Israel, have made her exploration of these issues even more acute and painful and necessary.

Let me tell you a story that goes to the heart of this question about being Jewish, about Zionism, about the establishment of Israel. In September 1982, there was a terrible massacre that occurred in Lebanon, carried out by the Christian Phalange with the aid and abetting of the Israeli Defense Forces under the leadership of General Ariel Sharon. It was the Shatila/Sabra massacres, and it was terrible. I was then deputy editor of the Sunday opinion section of the Los Angeles Times.

And I remember that after those massacres Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres, who was on the left and probably one of the more liberal people in the Israeli government, came to visit the Los Angeles Times. And as was the habit at the Los Angeles Times, he was invited to an elite luncheon that was composed of about fifteen people on the editorial board of the paper, and I was included. It took place at the tony Tamayo Room, which was kitted out with modernist mid-century furniture. Everything squeaked in that room. There was glass and leather and tubular steel Marcel Breuer chairs everywhere. Peres was seated in the middle of the table, opposite him was Tony Day, then the editor of the editorial pages. Next to Shimon Peres’ right, was his bodyguard. And to that man’s right was me. The salads arrived and we began to eat. I could barely take my eyes off the man’s neck. This was the neck of a Cossack. It was huge. I kept looking at his neck and I thought, my God, it’s not a Jewish neck. Six thousand years of Jewish history for this? And it reminded me that one of the goals, maybe the chief goal of the settlement of Palestine, and the creation of Israel in 1948, gathering all the moral authority that could be mustered in the aftermath of the Holocaust that had decimated European Jewry, was to secure the safety of the surviving remnant, to provide a state capable of defending the defenseless. So it was thought by many people who applauded it. So did the Soviet Union at the time, who voted for the establishment of the State of Israel, because this was going to be the national homeland for the Jews who otherwise were persecuted and were vulnerable everywhere.

And the remnant of European Jewry needed to feel they could defend themselves against the assaults of anti-Semites everywhere. The slogan went out that in Israel Jews could become a normal people in a normal state. And I thought, my God, is this neck the neck of a normal person? Or is this neck an almost biological betrayal of everything that I was taught was sacred and noble about the Jewish experience? Was this the neck of the people of the book? So what was the cost of normality? And that remains at the heart of the paradox and contradiction of Zionism. But all this hardly matters. You could argue until you’re blue in your face about who did what to whom, when, and you could have near Talmudic discussions about this. What counts is the emotional attachment that peoples on every side, each of whom are hostage to fanatics and fundamentalists and extremists, who believe with all their might that they have a near God given right to the same bit of desert, and they are going to squander their best, the flower of their youth sacrificed to a murderous rage, each claiming a right to live there. So, now we have 25,000 and counting deaths, many of them women and children. A murderous vengeance, criminally prosecuted by the power-mad Benjamin Netanyahu. Other extremists on the other side. And as the old slogan in the ‘60s had it, war is bad for every living thing. Now, we have a pretty forlorn and hopeless situation. What Israel has done in its acts of vengeance is simply sow the seeds for the dragon teeth that will arise.

Every Palestinian will seek revenge down the generations. The place is cursed. Reason has taken flight. Sobriety is nowhere to be found. And we have a fever dream of competing nationalist yearnings by two peoples who somehow cannot find a way to live together in peace and harmony. The squandering of the flower of their youth is a heartbreak for everyone. So is the question of the endangerment of Jews everywhere. I’ve never thought that Israel or the state of Israel spoke for everyone. I’m a disciple of I.F. Stone, who said that all governments lie, including governments that you might be attached to for emotional and historical reasons. So indeed in Israel, a greater debate has often occurred than is permitted here in the United States. To go back to the Jews of L.A. though, the thing that interested me when I was working with you on that series, was less what Lew Wasserman’s position was with respect to peace, and a just dispensation that would honor and recognize Palestinian hopes for statehood and, square the circle with Israel’s right to exist. If indeed it did have a right to exist, which is now questioned by many people.

Scheer: Listen, I got to stop you there because that is going to be the sentence that’s pulled out by whatever they’re called, the canary people or whatever. There are a lot of groups now that like to pick a couple of sentences and then show that this whole discussion has really been a denial of Israel’s right to exist or is anti-Semitic. So let’s interrogate that one statement because that’s exactly why we can’t have a debate now. You raise any complexity, and the argument becomes simplistic and irrational. So what do you mean by that? That Israel has a right to exist, you mean as a Jewish state?

Wasserman: Yes. I mean, if the chant “from the river to the sea,” is meant to say that Palestinians have a right to the land free of Jews, Judenrein, free of Jews, and that the Jews who are in Israel now, who consider themselves Israeli citizens, are, as the current vernacular has it, simply either the progeny…

Scheer: You meant the Palestinians, not the Jews?

Wasserman: No, I mean the critique is that the Jews…

Scheer: I’m going to stop interrupting you. Let’s start all over. Tell me what you meant by that statement.

Wasserman: The question of Israel’s right to exist has been debated since Israel established itself in its war in 1948, right? This question hangs like a Damocles sword over the entire existence of the state, and it is acutely painful and center stage now because of the events of October 7 and the ensuing violence, no?

Scheer: Yes.

Wasserman: But even without taking a position on that question, the question is on the table.

Scheer: Okay. Let me push this a little further. You said something very important. First, the drive for a normal life. And people should understand, at the heart of the condition of Jews in the Yiddish Pale, which was where many, even most Jews who ended up starting Israel came from, they weren’t from the Arab countries. Whatever you want to say, in the Arab and in Persia, Iran and so forth. Jews were not subject to the kind of genocide that was visited upon them by primarily Western Europe, but with a lot of support from Eastern Europe. Okay. And anti-Semitism was the most destructive force in human history as a targeted force. It was a product not of Islam or Arab world or the Persian world, but of the Western European experience and Eastern Europe. Okay, let’s put the whole of Europe at the heart of it, obviously Germany and Austria and so forth. And the irony is, and even though you didn’t experience the anti-Semitism in Oregon, anti-Semitism was quite strong in the United States. In fact, one of the things we pointed out in our Jewish series is the major social clubs in Los Angeles excluded Jews, which is why Jews felt they had to have Hillcrest and their own golf course because they couldn’t play golf at the major golf course and they couldn’t be in the Jonathan Club, they couldn’t be in the California Club.

And I can assure you, as a kid growing up in New York, I was punched in the face more than once because I was accused of killing our Lord or killing Christ. And it wasn’t until I was working at Ramparts magazine, a Roman Catholic literary quarterly, when I got hired there, that Pope John said we didn’t do it officially. So, for your father’s generation in New York, your mother’s generation, it was a live issue and including at our Christopher Columbus High School where not only did we think that Columbus had invented America and so forth, but we had to fend off anti-Semitic attacks from other kids. It was not an unusual part of our experience that the desire for a normal life that the words you use grew out of the fact that Jews were prevented from leading a normal life. They were not allowed very often to have land. They were not free in their total movements. That’s why you had the Yiddish Pale. And there was hypocrisy in both the Soviet Union and the United States, it’s not clear which one first recognized Israel, but they were the first two nations to recognize Israel. They didn’t have clean hands. Anti-Semitism was a very strong force, particularly after the elimination of Trotsky, who was Jewish, and anti-Semitism was a feature of communist life.

There’s just no question about it. And it was also a strong aspect of life in America. And there were prominent Americans who even had sympathy for Hitler. That was not a dead issue. And Roosevelt, when I was growing up, when I would run into more conservative kids, they even thought Roosevelt was Jewish. So the desire for normalcy is understandable. It means you want to lead a life and not be insecure all the time and yet pursue your religion, your tradition, and so forth.

And it was also, as I say, a convenient copout for the rulers of England and the United States and the Soviet Union to embrace Zionism. Good, the Jews who are troublemakers, they’re progressive, they’re radical, they write too much, they think too much. There is a wonderful tradition which you summarized before. They’re a threat to our stability wherever they are. Let them have a state of their own. Okay. So there was a cynicism that underwrote this, that Zionism could play on. Okay. The irony is, and that’s why I acknowledge that the people who ended up going to Israel basically did have a legitimate concern about their survival. They no longer trusted Germany where they had felt quite secure up until Hitler. The German Jews felt assimilated, despite anti-Semitism. So the irony that I encountered at the time of the Six-Day War is that I felt very close to the Israeli people. First of all, like even the kibbutz movement, which only represented three percent of the population that produced about eighty percent of the top officers of the army, the people who actually led things and sacrificed. It was the center of an idealism. It was basically a leftist experience.

Wasserman: And all those people have largely become politically irrelevant.

Scheer: Of course.

Wasserman: They’ve been defeated in Israel.

Scheer: As I always did in my career with you, I’m building on your original work here. So I’m going to end up agreeing with you. I just want to make it clear to anybody listening. We’re not denying that there was some need for normalcy.

Wasserman: Yet, despite the anti-Semitism that you rightly point out, no ethnic group has risen so far, so fast and found prosperity and a perch in American life as did the Jewish citizens of the United States. The very fact that I, the grandson of immigrant Polish and Russian Jews, became the literary editor of the Los Angeles Times, testifies to this astonishing rise. My father was a first generation American. My grandparents on both sides were immigrants that came to this country not speaking English. That their grandson became the editor of the Chandler family-owned Los Angeles Times, is incredible. Something like the first cut in Kubrick’s film, “2001,” where you have the ape throwing the bone into the sky and it becomes a spaceship. No other ethnic minority in the history of America since its founding ever enjoyed such a rapid rise into the highest reaches of American life in almost every sector. Despite the anti-Semitism.

Scheer: When your book comes out, I’m going to really have a good long podcast with you because we have some very interesting discussions and they quite often reflect even a generational difference. I would argue the ethnic group that had the highest rise was the German Americans, non-Jewish German. And Jewish-German Americans did very well, but still…

Wasserman: The interesting thing about our Jews of L.A. series, was that their fate was a triumph to the extent that Jews became powerful in Hollywood. They were outsiders. Neal Gabler in his book “How the Jews Invented Hollywood,” tells that story convincingly. What was interesting is that the Jews who came from the Pale, your grandparents, your parents, my grandparents, these were people in contradistinction to the German-Jews who were the merchant princes and the financial kingpins.

Scheer: They didn’t want us.

Wasserman: We reminded them of their messy origins.

Scheer: Yeah, there was no question about it.

Wasserman: It was the difference between Los Angeles and New York.

Scheer: Well, the irony is you talk about how your father went to Cooper Union, which was a full scholarship.

Wasserman: Full scholarship, of course. I once asked him where would you have gone had you not gotten into Cooper Union? He said City College.

Scheer: We had a very good engineering school. That’s where I also went. But your father was very smart and very good at what he did. You don’t mention he ended up working for Bechtel. He went very far.

Wasserman: I’m happy to mention it. At the heart of what my father wanted to do was a social consciousness. He wanted to build buildings and things for the masses. He became a hydroelectric engineer. At the time, it was thought dams would provide clean energy. Get away from nuclear power. You dam up the rivers. The Tennessee Valley Authority was the model. This was clean energy for the masses. What could be more useful? And I’ll tell you one thing about Bechtel. They never had a contract in Vietnam. It never associated itself with the war effort. On the other hand, yes, Bechtel helped build the pipelines with the Saudi royal family for the oil industry all over the world. They helped build oil refineries.

Scheer: It’s a typical Jewish experience because I remember having discussions with your father and mother when I was running for Congress on an anti-war position, and I’m talking to your parents, who I really like a great deal. I have tremendous respect for them. And your mother was really sort of a pioneer in physical fitness for women and their independence and assertiveness, and did it for most of her life. I remember talking to your father about Bechtel and, basically, what are you doing with Saudi Arabia? And it’s a typical, shtetl Jewish conversation of taking every position, wandering around every corner of every argument, and so forth. It was never boring. It was always open. Sometimes it got heated. But your father was very conscious of questioning whether he was living a life of contradiction? Is this the right thing to do? It was one of his defenses of taking his success as far as he could. And as I recall, retiring at a relatively early age because…

Wasserman: He retired at age 56. He died in November 2022 at age 92.

Scheer: Yeah, because he wanted to experience other aspects of life.

Wasserman: So he became the president of the Berkeley-Albany chapter of the ACLU, and was a proud member of the National Lawyers Guild. He slept in the national headquarters of the Black Panther Party to prevent police attacks.

Scheer: You should mention he went on to become a lawyer too.

Wasserman: Yes, and guess who financed it? Bechtel. He went to his employer and said I’m bored. I think I should become a lawyer. And why don’t you make an investment in me? Because I don’t have the money. You don’t pay me enough to go to law school. Why not make an investment in me and keep me employed. So he worked eight hours a day doing the job. Then going to night school for four hours. Meanwhile, his three kids were teenagers running amuck. My father did all this without complaint and seemed to extract joy. I never remember him coming home doing work, or working on weekends. I never saw him break a sweat. If I could be on my best day half the man my father was and half as ethical, I would die happy.

Scheer: Well, we could sort of wrap this up with that statement.

Wasserman: All my rebellions, Bob, were against much larger, more impervious institutions. They were never against my parents, who always put wind in my sails.

Scheer: And that’s true in my case, too.

Wasserman: Yes. I remember your mother, Ida.

Wasserman: “Bobby, what are you talking about here? What is the contradiction here?”

Scheer: Oh, my mother, when I wrote my rather flattering view of Nixon in the Los Angeles Times the only person that liked the article that I heard from was Richard Nixon. Absolutely amazing. This was my effort and objective journalism in the extreme. My taxes had been audited by Nixon. I considered him a war criminal. Nonetheless, I tried to step back and look at why he went to China? What did he really do in terms of ending the Vietnam War? What was his domestic program? He had Moynihan’s idea of a guaranteed annual income. He’d done the Environmental Protection Agency. Nobody ever to this day, mentions it’s a Nixon project. Nixon was a man of contradiction as well, and very much influenced by Eisenhower, who he has served as vice president. Today, he would be considered a leftist Republican in the extreme. Nixon certainly was not for shattering the federal government. Nor was he more of a warmonger than Lyndon Johnson or maybe Joe Biden, who’s certainly establishing a record in that department now. My mother was living with me in Orange County, and this was a very long article, and I was home that day. And so the article came out in the LA Times, and my mother read every word with her glasses, and she was already 85 or so reading, reading, reading. And then she looked up at me and she just said, only a single sentence: “He needs you?” I’ll never forget it. “He needs you?” And I said, yeah, Ma, he does. Because if we’re going to understand history, we must be fair. Yes, objective. We have to really look into it. Let’s talk about your parents. I wish you would write a memoir, because I think the generation of your parents who sacrificed—I was born in ’36—is important to understand.

I went right through the Depression and then the Second World War, and there was no group, despite the Hitler-Stalin Pact, pushing harder for U.S. entry to defeat fascism, beginning with Spain in 1936 and certainly agitated to open up the second front, which we did quite late, talk about the concentration camps, they were in full force, before we entered the war, and hardly any discussion of this Holocaust that was going on. It was an inconvenient truth to bring up, as it might divide people here. Everybody forgets we had a segregated armed forces and a lot of contradictions. But I can remember being schlepped literally, taking the train down to Washington to picket the White House to get the U.S. to enter the war.

Wasserman: When war was declared, my mother was the baby of her family. She had four older brothers and a sister. All four brothers served in the Second World War. I never met the two eldest, Max and Sam. I’m named after Sam. Steve, I don’t know how they got that from Sam. But that’s the story of the family. They were among the first to enlist. They’d been members of the American Communist Party. They had followed the events in the Spanish Civil War. They were, as the saying went, premature anti-fascists. They were eager to fight Hitler. And they were killed within a week of each other. One is buried in Belgium. The other is buried in a military cemetery in the States. My mother has never gotten over their sacrifice. So, yes, we shed blood in the war against fascism.

Scheer: We had a war memorial right there in the middle of the Coops and they got names on it and the gold star. But I do want to say, half of my family were Germans. And one of the confusing things was my uncle in Germany who was wounded in Stalingrad on the German army side. But the fact is, my German relatives in the United States, I know you and I have discussed this many times, were also premature anti-fascists. Because they were on the Left, I don’t want to label them. Some were Wobblies, some were socialists, some were more conservative and some were communists. I think my Uncle Edward was. I know my father was briefly kicked out because he didn’t want a wildcat strike and got denounced by my Aunt Lily. It’s a whole other family chapter. But it is interesting. I was just emailing with my nephew, my half brother, all German, and he was in the U.S. Air Force because the Germans were allowed to fight in Germany. The Japanese, if they weren’t in the concentration camps here, they were, and I use that word, maybe it’s excessive, but…

Wasserman: No, it’s precise.

Scheer: Yeah, rounding up innocent, loyal citizens of your society based on their racial or ethnic background certainly fits that description. But nonetheless my brother was trusted to bomb our home area of Germany. And he was in the U.S. Air Force, and he was interested in that. And I remember as a kid thinking of that contradiction, that the only thing that made my German family wonderful and decent and progressive, was that my German relatives never allowed an anti-Semitic or racist remark in their presence. And it was because they came out of the Left. No tribute was ever paid to that role of the Left of various shapes, including a pacifist Left, and of how important, among white people, they were to the civil rights movement.

Wasserman: I agree. I think it’s one of the great stories and I don’t think the full story of how the Left and, yes, the American Communist Party led the way on resisting racism in this country and was important in that struggle. That story has not really fully been told, not in the dimension it deserves.

Scheer: It’s only told as a negative story because the FBI went out to destroy Martin Luther King.

Wasserman: It’s told as a cynical ploy by this sort of fifth column doing Stalin’s work, in order to manipulate the legitimate desires of African Americans and to hold them hostage to this benighted foreign germ of communism. That’s the commonplace understanding.

Scheer: Yeah. And the irony is, at the university, when we are still paying tribute to W.E.B. Dubois, the fact of the matter is, and this is something that no one ever wants to talk about, he was 94 when he joined the Communist Party. Of course, he thought the Chinese were actually on the right road. And often you hardly ever hear of that. I want to end with one last thing. You have devoted your life to ideas. And when we did our Jewish series and it was our series, I don’t know, I hope you still respect it.

Wasserman: I respect it, I’m proud of it. And both of us had to flee the city into near internal exile because we arouse such enmity and wrath that descended on both our heads.

Scheer: But I do want to say something. There was an objection from Vivian Gornick. I have great respect for her. I knew her as a kid in the Bronx, and we went to City College. When we wrote that series, we quoted Vivian Gornick. She wrote me a note. She objected because we ended the series with a reference to this Yiddish teacher that I had had and Vivian had at shul. Sheen Daixel was his name. I’m taking this back to Heyday Books, We were playing Cowboys and Indians, even in a progressive neighborhood, we were killing Indians, okay? We didn’t know they were indigenous people. We accepted the whole modernization mystique everywhere in the world that industrialization would bring enlightenment. And we wanted machinery to come in and blah, blah, blah. But no one ever had a word to say about Native Americans that was positive, they were called savages in the American Declaration of Independence, right? And Daixel had spent time living with the Hopi, this Yiddish teacher teaching us Yiddish. Not Hebrew, but Yiddish, the language of our diaspora, of our struggle, of our survival, and was an incredibly poetic, dynamic teacher. She described him in her book, The Romance of American Communism, as having this bony hand grabbing her wrist. And, we quoted from her…

Wasserman: “Ideas, dolly, ideas. They’re the most important thing.”

Scheer: No. “With them, you have everything.”

Wasserman: Yes, “With them, you have everything.”

Scheer: “Without them, you have nothing.” Yes, now I’ve become your researcher.

Wasserman: You’re good.

Scheer: “Ideas, dolly. With them you have everything, without them you have nothing.” And to my mind, that describes what we were taught about being Jewish.

Wasserman: You have my wholehearted agreement. And it’s moving to think so. And I hope that the life I’ve lived will have demonstrated fealty to that idea.

Scheer: And, on that note, I want to thank, first of all, Steve, for doing this, Laura Kondourajian and Christopher Ho at KCRW, the wonderful NPR station, FM station in Santa Monica for hosting these shows. Joshua Scheer, our executive producer, who constantly tells me I’ve got to broaden my scope here. I think we did that today with an introspective look into our mutual history. I want to thank Diego Ramos, who does the introduction. Max Jones, who puts this all up in video form and somebody we haven’t talked about here, but you mentioned Grand Street, and that wonderful literary publication that Jean Stein put out…

Wasserman: She took it over from Ben Sonnenberg, who had founded it.

Scheer: Yeah. And she kept it going and Jean Stein, who was a great, I would call her a significant, public intellectual, even though she didn’t come on as the big intellectual. She came from one of the most important Jewish families where Lew Wasserman actually worked for her father, Jules Stein, who founded the Music Corporation of America (MCA). Jean Stein was actually the first person that really persistently and in a profound way challenged my own naivete about Israel. And I’ll use those words advisedly. I indulged the notion that the heart of the leadership of Israel was in the right place, and that they were being twisted by events. And yes, their opponents had an imperfect record and engaged in violence of this sort. We saw some of their opponents and, in the start of this new stage of the war, I always gave the leadership of Israel the benefit of the doubt.

Maybe in some ways I did it out of opportunism, because you get a lot of heat, if you dare challenge it. I think we’re in a moment now where it is just simply deeply immoral for anyone non-Jewish or Jewish, to give any nation a blank check, no matter what they call themselves. But as a Jewish person, and I do consider myself fully Jewish. And, I notice the religious interpretation. If you have a Jewish mother, you are fully Jewish. So let me take that. And I just think this is a moment in which you cannot remain silent and still call yourself a Jew. To my mind, that’s obvious. I’ll let you have the last word on that Steve Wasserman, but I did want to finish my tribute to Jean Stein, because in memory of Jean Stein, we get some funding for this show, which I very much appreciate. I think this particular discussion acknowledges my debt to her and through her friendship with Edward Said, a really important Palestinian scholar. She introduced me to him and to his work. I really feel that a lot of my thinking flows from her persistence in challenging me on this very issue. I’ll let you have the last word, Steve.

Wasserman: There’s much that I agree with what you said. And there are aspects I don’t agree with.

Scheer: Who would want it any other way?

Wasserman: I would say that your hyperbole is not conducive to a sober and unsentimental look at the nature of Jewishness. I, for my part, would not say that if you remain silent, you are not a Jew. Jewish people can be silent and they can be outspoken. They can be racist, they can be self-hating, they can be ugly, they can be beautiful. They can be handsome. They can be on the side of the angels. All of them are Jewish. Okay?

Scheer: Why Steve? I can’t let it go that way. Is it by religion? Is it…

Wasserman: Being Jewish has nothing to do with religion, it has to do with birth. You’re born into the tribe, and you are free to believe any cockamamie crap you want to. You could become a fascist and other Jews would, perhaps, I hope, denounce you for that. You could become a self-hating Jew and mask your identity and join the Nazi Party, you’re still Jewish. Jewishness has nothing to do with your fealty to religious precepts, to something called Judaism, to whether it’s Conservative or Reform, or whether you’re agnostic or atheist, you’re still Jewish. The nature of Jewishness transcends political position or religious theology. That is a determination that the Nazis certainly adhered to when they put everybody into the ovens, no matter what their victims believed, no matter what their class was, all of them were regarded as Jews, all were fit for the ovens. I reject entirely this notion that if you remain silent, you’re no longer a Jew. Let’s condemn them on other grounds, but not on the grounds of ethnicity.

Scheer: Okay.

Wasserman: I take great exception to that.

Scheer: Maybe we should do a part two on this.

Wasserman: Let me ask you a final question, Bob. Do you think that the state of Israel has a right to exist?

Scheer: Good question. I do, but not as a guaranteed religious majority. I believe in one person, one vote. I believe that all people are equal. But you asked me a very good question.

Wasserman: Do you believe that Israel has a right to exist as a Jewish state?

Scheer: No, I don’t think any state has the right to exist by an artificial majority. I think that’s inherently an undemocratic idea. And let me persist a little bit here. At the end of the day, it’s up to anybody, whether they’re a convert or anybody, to make their own definition of what this label stands for. You did it with a certain amount of energy just there. And, let me say, it’s not the first time. Let me beg to differ. I think there are claims made on what that label means. There’s a religious claim, for example. Yes, and it’s not a simple one. There are different variations of Orthodox. The two main American worship standards or synagogues, the Reform and even the Conservative are not really accepted in Israel or without authority or certainly without religion. But I do think from much of the Jewish experience in this world.

And you don’t have rabbis in your family, I have a long line of rabbis on my mother’s side of the family. That’s what my mother rebelled against. And she then rebelled against the Bolsheviks. That’s why she came here after the Russian Revolution. My mother was a true freethinker by every standard. Nonetheless, there are different claims to what that word means. I think, at the core of it would be some sense of obligation to a standard of truth or decency, or values. Whether you’re coming from the religious or the secular or the tribal, there’s a claim that either through experience or through scripture or something, that there is some wisdom, there’s some meaning. And I think that’s why Jews show up disproportionately in social movements for improving society. I think there is a shared sense of obligation. You can call it tribal, a tribe that has suffered much, right? A tribe that has been forced to live as orphans in a hostile diaspora. I don’t think it’s just a matter of mindless rhetoric on my part to say that all of these different Jewish groups, including the ones I very strongly disagree with, do make a claim to some essential Jewish values.

Wasserman: The logic of what you’re arguing—and I understand it—suggests that the claim of a Jewish homeland in the form of a state of Israel, is not one you would embrace because it hollows out democracy. By the same token, would you also oppose a Palestinian state?

Scheer: Let me just go a step further and it not only hollows out that. It hollows out the religious notion.

Wasserman: Fair enough. But by the same argument, would you oppose a state that has voted for the enshrinement of Palestinian nationhood?

Scheer: Excuse me?

Wasserman: On the same basis on which you are deeply skeptical or even opposed to the notion of a Jewish state.

Scheer: Okay. And since we all believe in rational and full discussion, I’m going to take this time now to engage in this because I don’t want to go swapping slogans. Okay?

Wasserman: I’m not making a slogan.

Scheer: No, let me just be clear. First, the religious claim is also one that exceeds secular arrogance and says, originally it’s not supposed to be even secular people who decide where you have Israel, it’s the return of the Messiah. But leaving that aside, I have no objection to a Jewish state when there’s a majority of Jews. As long as they follow recognized international rules for the rights of the minority in any community, yes. If Israel had not expanded and kicked out people in the Nakba or if the Palestinians had just been there and there hadn’t been this great flood of refugees and people coming in, yes. I believe there should be a state for the Kurds, for example. I’m not opposed to Chechnya’s independence or Georgia’s in that particular piece of real estate, I’m not a big nationalist.

I’d like to see more of a one world experience as implied by the formation of the UN. Nonetheless I think you once used the phrase geography is fate, so yes. This also relates to population. See, I did learn from you, Steve. Geography is fate. But I do believe, yes, as a pretty good rule of thumb, whatever people happen to be living in a designated area, however developed, if you follow the principle of one person, one vote, you prevent discrimination. You guarantee equal human rights. And if a majority of them happen to be Kurds or are Jewish or Palestinian, and they vote for people that are sympathetic to that so long as it’s not coercive, and don’t have an established religion and follow basically principles of minority rights and so forth, then I say you could call it whatever you want to call it, as long as you follow those principles. The contradiction with Israel is that they favored a geographically expansionist policy.

The Israel that I visited in 1967 at the time of the Six-Day War, was at least aware that it would fail as a society if it did not guarantee the Palestinians then living, whether they were Christian or Muslim or anything else for that matter, others, there were other people living there. If they did not fully recognize, all the ones I talked to, their rights. Now, they weren’t in the army but that also would have to be the Palestinians contributed blood to the Israelis, a number of them, in Israel. You don’t put the question properly. The question is whether people can have societies in which one religion or one ideology or whatever is representative of a majority. We certainly have lived that reality in the United States with white, basically Anglo Saxon people, basically Christian. But we have enshrined in our Constitution, rights, not always exercised fully, the rights of minorities and the fundamental rights or human rights of every individual, so they can’t have religion imposed upon them.

If you ask me, do I believe in a Jewish state with religiously derived laws and going to rabbis to determine what laws? No, because that’s fundamentally a denial of the rights of other people. If what you really mean is a state where a majority of people—not by coercion, by ethnic cleansing, by fascist repression—happen to be a majority of Jewish people, then yes. If you’re pointing out the contradiction of defining it as something called a “Jewish state,” meaning not as a description of the demographics, but rather the imposition of something called Jewish law or Jewish preference or Jewish favoritism, then I’m against it because it’s fundamentally undemocratic. And so would a Palestinian state be, if that is what you’re talking about. That would mean non-Palestinians’ vote matters less or their rights are not as important or equal, then yes, I’d be opposed to a Palestinian state.

Wasserman: We find ourselves in agreement on both of these questions.

Scheer: We’ve gone a little further with this last discussion, but I think we should leave it in. We could edit it out, but I think we should leave it in.

Wasserman: As you wish. These questions beg to be asked. The answers are often elusive. But hopefully we’ve been able to ask some of the right questions that challenge both our positions in ways that will deepen our thinking and give us greater insight and perhaps that most elusive of virtues—wisdom.

Scheer: Well, there you go, Wasserman, with the pithy quote at the end that we can use. That’s how you saved some of my writing. Okay, I’ve already done the thank you to everybody and I’ll see you next week with another edition of Scheer Intelligence. And look for Wasserman’s book coming out in October.

Wasserman: Yes, it’s called “Tell Me Something, Tell Me Anything, Even If It’s a Lie.”

Scheer: Okay. And check out Heyday’s catalog. It’s really a marvelous publishing effort, yes. Take care.

Robert Scheer

Robert Scheer, publisher of ScheerPost and award-winning journalist and author of a dozen books, has a reputation for strong social and political writing over his nearly 60 years as a journalist. His award-winning journalism has appeared in publications nationwide—he was Vietnam correspondent and editor of Ramparts magazine, national correspondent and columnist for the Los Angeles Times—and his in-depth interviews with Jimmy Carter, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, Mikhail Gorbachev and others made headlines. He co-hosted KCRW’s political program Left, Right and Center and now hosts Scheer Intelligence, a KCRW podcast with people who discuss the day’s most important issues.