By Mark Lloyd / Original to ScheerPost

On June 16, 2023, the White House announced that President Biden was proud to have signed the 2021 bi-partisan law establishing Juneteenth as a new Federal holiday to, in his words, “commemorate America’s dedication to the cause of freedom.” Juneteenth, in many ways, is the quintessential American holiday. Even Marjorie Taylor Greene is celebrating, telling Newsweek: “I’m in support of celebrating important days in American history and the emancipation of slaves is important. Plus, any day that we can shut down the federal government is a good day for the American people.”

If the story of Juneteenth is fully told, it might help all Americans see the complex and contradictory and joyful and painfully ugly side of a nation still at war with itself and its ideals.

June 19 – Juneteenth – was first celebrated in Texas; it has been called Freedom Day, Jubilee Day, Juneteenth Independence Day and Black Independence Day. According to Annette Gordon-Reed, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and author of “On Juneteenth,” Black Americans in local communities across Texas insisted on taking June 19th off, and pushed Texas to become the first state to declare it a holiday in 1980.

You can also make a donation to our PayPal or subscribe to our Patreon.

Texas Governor Greg Abbott began his 2023 celebration of Black Independence Day by signing a bill to eliminate diversity, equity and inclusion offices and programs in colleges and universities in Texas, this was in keeping with the 2021 bill he signed to limit how teachers discuss the fight for racial equity in the United States. Yet in 2022, Abbott issued a Tweet on Juneteenth encouraging Texans to “reflect on our shared history & join together in working toward a brighter future for every American.” Conservative supporters of Abbott argue that bills he signs are only protecting the history that should be shared, while opponents argue that his actions will ensure that students will learn only a distorted history of slavery in the Lone Star state. And so, the civil war in Texas goes on.

Perhaps we should back up.

In the late Spring of 1865, Union General Gordon Granger and his troops were ordered to bring the District of Texas under full Union control. The Confederate capital of Richmond had fallen, and Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox to Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in April, but several other Confederate forces — some large units, some rag-tag bands — had yet to surrender. And so on June 19 at Galveston, Granger issued a set of military orders, the 3rd of which was General Order No. 3. The last sentences of the third order is often edited out but it is worth reading to understand something of the challenge awaiting the nation:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

No, Granger’s freedom was certainly not the independent freedom promise of 40 acres and a mule.

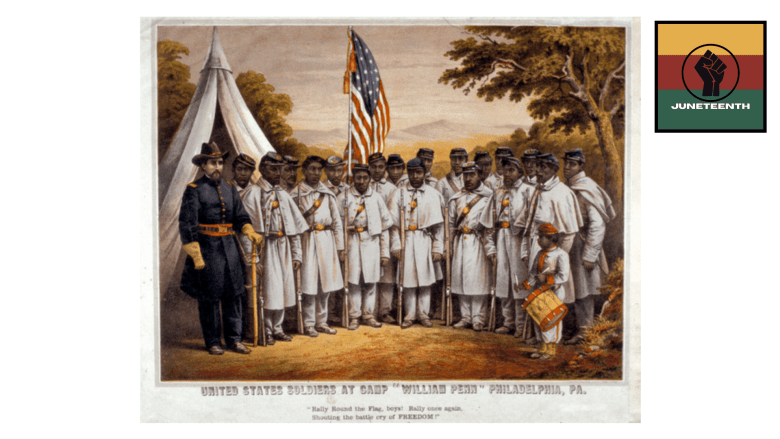

Gen. Granger did not personally deliver his message encouraging quiet submission to former masters to the approximately 250,000 people held in slavery in Texas; it was the Black soldiers in his unit who spread the news, reading the military orders in courthouses and churches. In 1865, Black troops were essential in conveying the important hope of a new day in America, and protecting the population of people held in bondage from those who would brutalize and exploit them. Yes, Jubilee! Black Independence Day had come . . . but, no, it would not last.

In fact, the Civil War, which had morphed from a war to preserve the union to a war to end slavery, would not be declared over until August 20, 1866. That task fell to President Andrew Johnson, as President Lincoln was assassinated four months after pushing through Congress the highly controversial 13th Amendment in 1865. But, again, the Civil War did not really end, it simply shifted battlefields. The Confederacy, the southern slavocracy, would lead a successful battle over public opinion, and turn the war against slavery into a war of northern aggression, a war against state’s rights. The Ku Klux Klan rose and Reconstruction was defeated in Congress. Abolitionist reformers would be called carpetbaggers and General Lee would be mounted on pedestals and hailed a national hero and not a traitor, and teaching otherwise would become… well, we now get back to Governor Abbott of Texas. No, the Civil War over the place of Black Americans has not ended.

But we should not forget, slavery was a stain across all America, not just the south and not just brutalizing Blacks. Recent research shows that hundreds of Black Americans remained enslaved in New Jersey at the end of the war. There was also slavery in the union-loyal border states of Delaware, West Virginia and Kentucky long after Juneteenth. In addition, Western states, such as New Mexico, Oregon and Utah also tolerated slavery, including the enslavement of Indigenous people. In California, the enslaved included Blacks, Indigenous people, Chinese, Sonoran, Chilean, and Hawaiian laborers, and a significant number of Chinese women were enslaved in the sex trade. Despite the fact that slavery was against state law, slave owners in the West simply didn’t tell their captives that they were free, and the state did not enforce laws prohibiting slavery. Juneteenth did not change this.

Yes, our shared history is quite complex. Not only was the Emancipation Proclamation limited to emancipation in the South, it has long been constitutionally suspect. And because the seemingly straightforward 13th Amendment allows slavery as a punishment for crime, several states began creating crimes resulting in what historian Douglas Blackmon and others have called slavery by another name. Perhaps the beginning of the U.S. prison-industrial complex.

According to World Population Review, as of March 2023, the United States has the largest population of incarcerated people in the world (and no it does not have the highest population), and Texas (the Juneteenth state) has the highest incarcerated population in America. Black Americans are disproportionately represented in the prison population. The historically brutal relationship between Black Americans and the U.S. criminal justice system was made obvious through the murder of George Floyd.

Rep. Barbara-Rose Collins introduced the original call for a Juneteenth national holiday in 1996. Twenty-five years later, a young bystander in Minneapolis, Minnesota, shared a video she recorded on her phone of a white police officer kneeling on the neck of Mr. Floyd (a man accused of passing a fake $20 bill). The protests that followed were largely responsible for the bi-partisan support in 2021 for a national Juneteenth holiday.

On June 16, 2023, U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland issued findings into the conduct of the Minneapolis Police Force, declaring the department to be systemically racist against both Black Americans and Native Americans. Even as the President lauded the bipartisan bill creating the Juneteenth holiday, he issued another statement touting the “Executive Order to advance effective, accountable policing and criminal justice practices that will limit racial profiling, build public trust and strengthen public safety.” Biden then called on Congress to pass the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act. No action yet. This is all old news to Black Americans.

The killing of George Floyd created an increase in support for the century-long battle against anti-Black racism in the criminal justice system, but that support has faded among white Americans. The historic impact of U.S. policies regarding Black Americans are reflected not only in treatment in the criminal justice system. There are tragic Black and white disparities in health outcomes, wealth and education.

In the meantime, the violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, praised by the leading Republican candidate, is now largely dismissed by a majority of Republicans as a legitimate protest. The tide of this particular civil war has only encouraged the growth of networks of white supremacists and far-right extremists who have expanded and broadened their presence online. Communities of color and Jews fear for their safety amid a continued rise in reported hate crimes in the first half of 2022, including shootings motivated by white supremacist ideology.

None of this should be surprising. While many whites deny systemic racism, they hold steadfast to the belief in race. Ignoring the general consensus of anthropologists, biologists, geneticists and other scientists who have for many decades now tried to tell us that race is a social construct, not a biological fact. And yet, still, police, doctors, bankers, teachers, journalists, indeed the vast majority of Americans of all colors and classes, regions and religions, continue to believe in the fiction of race – the idea that what W.E.B. Du Bois called “skin, bone and hair” are predictors of intelligence or any other measure of merit. The fiction of race is, perhaps the most damaging legacy of slavery. Perhaps, any celebration that slavery is really in our past may be a bit premature.

But, yes, let’s celebrate Juneteenth. Let’s learn the complicated lesson of Juneteenth, and keep hope alive that we are on the road to finally conquering the vestiges of the brutal American past. But keep our eyes on the prize. The civil war in America continues.

Mark Lloyd

Mark Lloyd is a communication lawyer and a journalist. From 2009-2012 he served as an associate general counsel at the Federal Communications Commission, advising the Commission on how to promote diverse participation in the communications field with a focus on research into critical information needs and broadband adoption by low-income populations. He now teaches at McGill University.